CAMA - The Future of Residential Municipal Valuations

The face of municipal valuations is set to change drastically as a computer-assisted mass appraisal (CAMA) increasingly comes to the assistance of human valuers to establish the market values on which municipal rates will be based.

“CAMA is basically the use of statistical methods – specifically multivariate regression analysis – to estimate the market value of a property”, says valuation head Llewellyn Louw of property economists and valuers Rode & Associates.

CAMA was used with great success in the 2001 general valuation (GV) of the City of Cape Town’s residential properties. In the USA, this technique has for many years been the accepted approach in numerous cities, including New York City.

To illustrate how CAMA works, we’ll use a highly simplified example of a block of flats. For simplicity, let us assume that all of the units in this block are the same in all respects, except for size. Hence, theoretically, the difference in market value between the various units should be a function of unit size only.

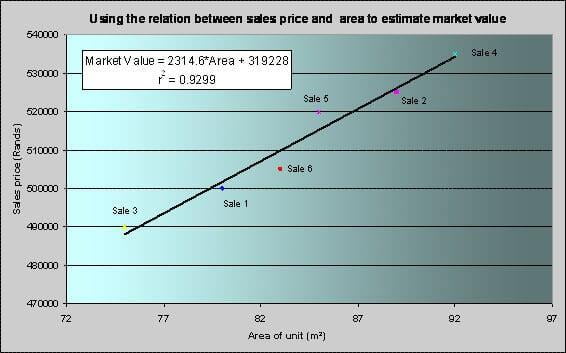

Assume further that recently the following six sales took place at our hypothetical block of flats:

If we plot these sales on a graph, we note that there is a strong positive relationship between the sales price and the corresponding size of a unit. The goal of CAMA is to identify such relationships and to express them as an equation.

In our example, it is evident that there is a linear (straight-line) relationship between sales price and the area of a unit. By using an appropriate software package, one can calculate the equation for the line that best fits the data. In our example this equation is:

Market Value = 2314,6*Area + 319228

One can now use this equation to estimate the market value of any unit in our hypothetical block of flats. Let’s say we want to calculate the market value of a unit with an area of 88m².

Market Value = 2314,6*88 + 319228 = R522.193 (say R522.000)

In reality, of course, there are likely to be a number of variables (or predictors) that explain the difference in value between the units in a block of flats, or between houses in a suburb. Some of the other predictors of value may be:

- Plot size

- Size of outbuildings

- Area of house

- Quality of construction materials and finishes

- Condition of overall property

- View

- Topography

- Neighbourhood

- Proximity to a busy street

A CAMA model could include any combination of these variables, and other variables. The benefits of CAMA when it comes to the large-scale valuation of residential properties in a municipal district, says Louw, is that it is cost-effective and reduces the potential for human error and inconsistency that could, for instance, result where more than one valuer would be required to cover a particular suburb.

“A key CAMA benefit is that it is obviously much better and more consistent than the human mind at identifying and weighting the contribution of the individual predictors to the value of a property. This is particularly so in the case of mass or large-scale valuations, where it is imperative that equity is achieved across the board.

“In view of the fact that the new Municipal Rates Act requires the revaluation of all properties every four years, CAMA would also result in great cost savings for municipalities.”

He cautions that, as always, the garbage-in-garbage-out principle applies. Great care must, therefore, be taken that the models are well specified and that the quality of the data upon which the models are built is flawless. It is, therefore, not a good idea to use data collectors who are not experienced and well trained.

CAMA works well in approximately 85% of cases, but given the nature of regression, valuer intervention will be required in the case of heterogeneous (diverse) neighbourhoods such as Clifton in the Cape Peninsula or Sandhurst in Johannesburg. Because few houses in these neighbourhoods are similar, and few sales take place, the market tends to be “inefficient”. This means there are great differences in prices because imperfect information is available to the market. However, as Louw points out, “manual” valuation approaches encounter the same problems in heterogeneous neighbourhoods.